Louise Hooper of Garden Court Chambers explains that social media concerns that changes to the law mean that the Government has the power to force vaccines or other medication on you are wrong and unfounded.

Since this article was written the legal position has significantly changed.

There are multiple human rights and civil liberties implications both globally and domestically arising from the response to COVID-19 and the current crisis. Some of them are very real and concerning. Others are scaremongering and simply not true.

There is a video doing the rounds on social media which states that changes to the Control of Disease Act 1984, which came into force on the 27th April 2020 regarding vaccines and Covid-19 medical treatment, mean that the Government has the power to force medication on you and that this means vaccines. This is not correct and I set out below where the information in the YouTube video came from and why it is a misinterpretation or wrong.

I also try and explain what Schedule 21 of the Coronavirus Act 2020 does do, as it provides wide ranging powers to require a person to undergo screening and assessment, to provide documents, information and answer questions, and if found to be infectious enable quarantine, isolation and contact tracing. All of these powers have the potential for abuse and must be exercised only where necessary and proportionate.

In the context of a major pandemic responsible for the deaths of thousands of citizens that currently has neither cure nor vaccine, it is clear that a major, enforceable, public health effort is required for the protection of health and prevention of death. It is essential in this regard that misinformation is not spread throughout the community. The Government has set up the Counter Disinformation Cell for this purpose. It would be of much greater benefit to the public if the Government’s attempts to ensure that accurate, honest information was reaching the users of social media platforms were focused on countering clearly inaccurate statements such as those in this YouTube video rather than, for example, trolling legitimate human rights organisations on twitter see eg. here.

The video

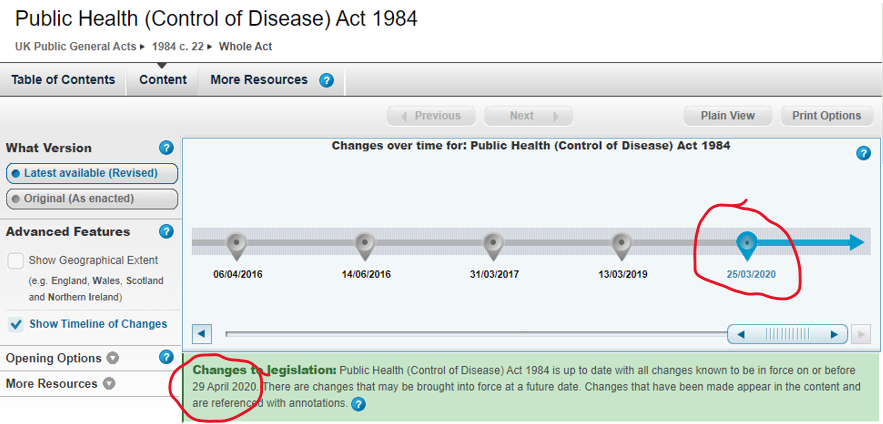

The video is a little confusing as it is not always clear what the presenter is referring to and some of it is not a correct interpretation of the law. I have been unable to find any amendments of the Public Health (Control of Disease) Act 1984 or Coronavirus Act 2020 made on 27 April 2020.

Looking at the link that is included with the YouTube video it appears that what the presenter is referring to is the band across the top that states that the webpage is up to date as of 27 April 2020 (on my version it is 29 April 2020). In fact, the last amendments were 25 March 2020.

It is important to be clear that some of the quotations in the YouTube video are from an article in the British Journal of Medical Practitioners from 2009 and not from any coronavirus or other public health legislation.

The example of forcible treatment refers to a news article about a man detained in hospital in relation to Tuberculosis in 2007. The parts of the 1984 Act under which that took place (s.37-8, removal to a hospital and detention in hospital) were repealed by the Health and Social Care Act 2008 (s129-130, effective 26 June 2010). This introduced sections 45A-T to the 1984 Act which gave the relevant minister the power to make regulations to prevent danger to public health and prevent the spread of infection.

The Act makes explicitly clear that the power to make such regulations does not include mandatory treatment or vaccination.

45E Medical treatment

- Regulations under section 45B or 45C may not include provision requiring a person to undergo medical treatment.

- “Medical treatment” includes vaccination and other prophylactic treatment.

Has the Coronavirus Act 2020 changed this?

No.

Powers to make regulations in England and Wales are made under and subject to the restrictions in the 1984 Act.

The Coronavirus Act 2020 introduces separate powers for Scotland and Northern Ireland to make health protection law under their devolved powers. These ensure that a similar prohibition on powers requiring mandatory medical treatment including vaccination and other prophylactic treatment is in force. They can be found at:

- Schedule 18 for Northern Ireland. New section 25E inserted into the Public Health Act (Northern Ireland) 1967

- Schedule 19 for Scotland. Permits Scottish Ministers to make Regulations in Scotland and paragraph 3 ensure this is subject to the same prohibition as that in the 1984 Act.

The Act enables a wider range of professionals in Scotland to administer vaccinations than previously permitted under the National Health Service (Scotland) Act 1978.

What powers does Schedule 21 of the Coronavirus Act contain?

What Schedule 21 of the Act does do is provide extensive powers to public health officials, police and immigration officers that exist for the period that the Secretary of State has declared that:

- coronavirus constitutes a serious and imminent threat to public health in England, and

- that the powers conferred by the Schedule will be an effective means of delaying or preventing significant further transmission of coronavirus.

To take into account issues relating to devolved powers similar provision is made for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland by virtue of parts 3-5 of the Schedule. The following analysis relates to the powers as they are set out for England.

These powers exist in respect of a person who is potentially infectious which means:

(a) the person is, or may be, infected or contaminated with coronavirus, and there is a risk that the person might infect or contaminate others with coronavirus, or

(b) the person has been in an infected area within the 14 days preceding that time. (Sch. 21 §2(1))

All of the general powers are only exercisable where:

- both necessary and proportionate and

- in the interests of the person, or for the protection of other people, or for the maintenance of public health.

Power relating to screening and assessment

- Direct or remove a person to a place suitable for screening and assessment (§§ 6-7) with a requirement that the person must be informed of the reasons for the direction/removal and that it is an offence, without reasonable excuse, to refuse to comply or abscond;

- Detain the person if there are reasonable grounds to suspect that person is potentially infectious for up to:

- 48 hours if a public health officer,

- 24 hours if a constable (can extend for a further 24 hours) (§13(2)

- 3 hours if an immigration officer (can extend for a further 9 hours) (§13(3))

- Require the provision of a biological sample or to allow a healthcare professional to take a biological sample which includes a sample of blood or respiratory secretions (including a sample taken by a swab) (§10(2));

- Require the person to:

- answer questions and provide information about their health or other relevant matters (including travel history and other individuals with whom they may have had contact) (§10(2)(b))

- produce any documents which may assist in their assessment (§10(4)(a))

- provide contact details for a specified period (§10(4)(b))

- Following screening the public health officer can direct or remove the person to another place suitable for further screening or assessment (§11(1)) and it is an offence to fail to comply with a direction or abscond from the place (§11(2)).

Powers after screening and assessment

Following assessment, if screening confirms coronavirus infection or contamination or was inconclusive, powers are granted to a public health officer under §14 to impose further restrictions and requirements for a maximum period of 14 days (§15) although there are limited provisions for extension. The person must be notified of the restrictions and that it is an offence to refuse to comply or abscond (§14 and §23). All restrictions must be reviewed within 48 hours.

The restrictions or requirements include:

- to provide information (§14(3)(a));

- to provide contact details for a specified period (§14(3)(b));

- to go for further screening and assessment to another place (§14(3)(c));

- to remain at a specified place or in isolation for a specified period (§14(3)(d)-(e));

- in respect of remaining at a specified place or isolation regard must be had to the person’s wellbeing and personal circumstances (§14(6))

Restrictions can be imposed for a specified period on:

- movements or travel (within or outside the United Kingdom) (§14(4)(a));

- activities (including their work or business activities) (§14(4)(b));

- contact with other persons or with other specified persons (§14(4)(c)).

The requirements or restrictions must be revoked if:

- the person is considered to be no longer potentially infections (§15(8)); or

- the requirement or restriction is no longer necessary or proportionate (§15(9))

Where a restriction or requirement is imposed it can be enforced by a constable or public health officer (§16). Public health officers, constables and immigration officers have an additional power to give ‘reasonable instructions’ in connection with directions or removing or keeping a person at a place and are required to inform the person of the reasons for such an instruction and that it is an offence not to comply with it.(§20)

Anyone who has a requirement or restriction imposed, varied or extended can appeal to a magistrates court. (§17)

There are additional powers in respect of children directed at the individual with responsibility for the child who must so far as practicable secure that the child complies with any direction, instruction, requirement or restriction given to or imposed on the child. (§18))

The exercise of the powers must be undertaken with regard to any relevant guidance.

It is an offence punishable in the magistrates’ court with a fine of up to £1000 to:

- fail without reasonable excuse to comply with any directions, reasonable instruction, requirement or restrictions given to or imposed on the person;

- fail without reasonable excuse to comply with a duty placed on an individual with responsibility for a child;

- abscond or attempt to abscond whilst being removed or kept at a place;

- knowingly provide false or misleading information in response to a requirement to provide information;

- obstruct a person who is exercising or attempting to exercise a power conferred by the Schedule.

Schedule 22 provides further powers relating to events, gatherings and premises. For the purposes of preventing, protecting against, delaying or otherwise controlling the incidence or transmission of coronavirus or facilitating the most appropriate health care response, events or gatherings can be restricted or other requirements imposed and premises can be closed.

Conclusions

It is clear that mandatory medical treatment and vaccination are explicitly prohibited by the Act. There is, however, potential for abuse leading to infringement of civil liberties and human rights unless the powers contained in the Coronavirus Act are exercised lawfully. The YouTube video, whilst correctly identifying some of the powers above fails to refer at all to the limitations on those powers.

Powers under the act are restricted to those circumstances where the exercise of the power is proportionate and necessary and for the shortest time possible. What is ‘reasonable’, ‘proportionate’ and ‘necessary’ is likely to change over time and is open to interpretation. For example, it may well be a proportionate measure for the State to detain an infected person who refuses to self-isolate until they are no longer infectious to prevent them passing on a disease which may kill another person.

That said, serious questions remain whether the UK’s response generally has been sufficient in light of the known threat to life under article 2 ECHR, the underfunding of our health services, the lack of PPE for medical staff and care workers, general lack of preparedness and the apparent disproportionate impact on BME communities. Abuses of power in respect of the Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) Regulations 2020 have already arisen.

If contact tracing apps are introduced there may be additional significant concern as to the use of data from those apps to determine ‘reasonable suspicion’ under this legislation particularly given the potential for algorithmic bias.

As with any legislation dramatically affecting civil liberties there is a need for vigilance to ensure the State does not overstep its boundaries and an effective remedy when it does so.

This article has been quoted by BBC Reality Check and Reuters.